|

Will The EM Trade Unwind & Can Policymakers Cope?

Following on from our article last week (Risk Repricing Yet To Trigger EM Capital Flight) in which we argued that there is little evidence (so far) of EM capital flows reversing, two questions naturally follow: will the EM trade unwind and can policymakers cope if it does?

Fig 1. EM ETF Flows, 3m % Change

Source: MNI, Bloomberg

As we previously highlighted, over USD1trn in net portfolio capital poured into emerging markets over the past decade, while evidence from higher frequency ETF flow data suggests that the recent bout of EM turbulence has not been sufficient to dislodge foreign capital.

Fig 2. EM Portfolio Inflows, % of GDP (4QTR Rolling)

Source: MNI, OECD, IMF, Bloomberg

Following numerous boom-bust cycles, the idea that collapsing local asset values and/or rising US rates triggers capital flight from emerging markets has become the conventional wisdom. However, this line of reasoning may no longer hold. The emerging markets of today are far removed from the emerging markets of 20 years ago. Except for a small number markets that have not heeded the lessons of the past (Argentina, Turkey and Brazil), most emerging markets are now better managed, have improved institutional credibility and stronger buffers against external funding stresses.

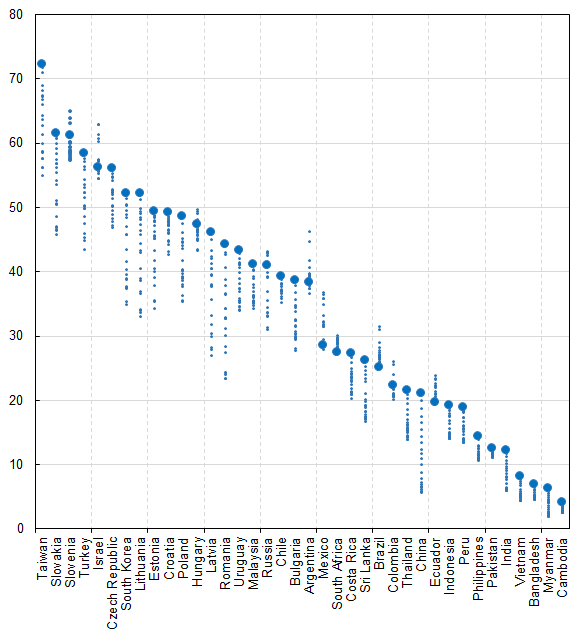

In many cases the emerging market classification is arguably redundant altogether. Poland, Czech Republic, Chile and South Korea now more closely resemble developed markets, albeit at a lower level of per capita income. To illustrate this theme, the chart below shows the extent to which productivity (defined in terms of labour output per hour worked) has converged with the US economy over the past twenty years. With the exception of Turkey, the economies positioned in the upper left quadrant are mature emerging markets that are far removed from the unstable and poorly managed economies of two decades ago.

Fig 3. Labour Productivity Per Hour Worked, % of US (20YR Range & Current Level)

Source: MNI, The Conference Board

With that in mind and considered alongside the prolonged economic stagnation and political instability plaguing many developed markets, it is not obvious that capital will flee emerging markets this time around. Again, while there are specific cases where there is a risk of ‘sudden stops’, more broadly emerging markets have evolved and can no longer be considered as a homogenous bloc that is susceptible to the same historical risks.

EM Central Banks Have Also Evolved

Even if foreign capital were to bolt for the exit, central banks are better prepared today relative to the past. The confluence of EM crises in the late 90s/early 2000s (East Asia 1997, Russia 1998, Argentina 2001, Turkey 2001) triggered an FX accumulation spree among EM central banks looking to strengthen buffers against external funding pressures.

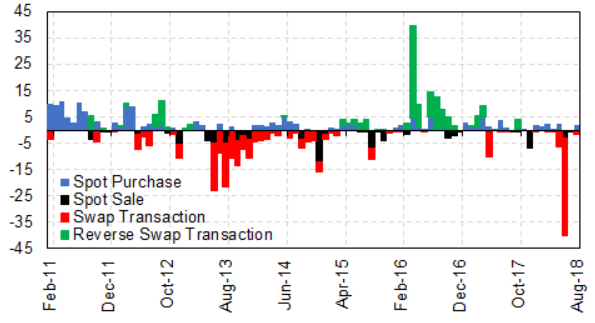

Moreover, in the face of potentially destabilising currency weakness, some central banks have deployed more sophisticated alternatives to traditional intervention in the spot FX market. Brazil, in particular, has become accustomed to using BRL-denominated FX swaps to provide synthetic dollars to the market (for hedging and liquidity purposes), which has served as an important pressure valve during periods of heightened financial instability. Although such non-traditional forms of FX intervention are by no means a panacea in the face of sustained capital flight (see the technical annex below with respect to the functioning of BCB swaps), it is nonetheless reflective of how central bank policy has evolved since previous boom-bust cycles. We believe that non-traditional interventions willfeature more prominently going forward, with Mexico appearing to be a recent convert.

Fig 4. International Reserves Adjusted For FX Forwards/Swaps, USDbn

Source: MNI, IMF

The more fundamental question on the adequacy of central bank resources for dealing with capital outflows is difficult to answer with any confidence. While measures of reserve adequacy are useful for evaluating the relative vulnerability of different economies, in absolute terms the metrics are deeply flawed given the arbitrariness of threshold levels. The chart below shows the gap between headline FX holdings and reserve adequacy calculated by the IMF (incorporating broad money, short term debt at 1-year maturity, exports and portfolio and other investment liabilities). China in particular stands out given that the reserve gap appears to be deeply negatively despite the PBOCs USD3trn war chest (reflecting the sheer scale of the broad money supply and ignoring the limited permeability of the capital account).

Fig 5. Headline Reserves – IMF Reserve Adequacy Level, % of GDP

Source: MNI, IMF

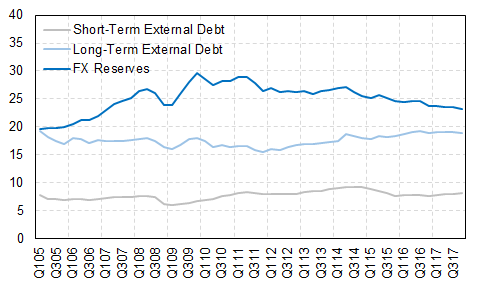

If it is the case that most of the major emerging markets are not at risk of sustained and destabilising capital flight, then the current stock of FX reserves held by central banks is likely sufficient to smooth out the inevitable capital leakage that will occur as US rates continue to rise and EM credit risk reprices.

Fig 6. EM Aggregate FX Reserves & External Debt, % of GDP

Source: MNI, World Bank, IMF, Bloomberg

Annex: A Note on the BCBs FX Swaps:

The BCBs FX swaps allow investors to hedge inflation and exchange rate risk, while also providing liquidity to the market. In reality, the instrument is more akin to a non-deliverable forward with a bullet-type payment structure rather than a swap with periodic cash flows. In addition, the BCB contracts settle in BRL (reflecting prohibitions under the exchange rate system) rather than USD and does not involve an exchange of notional. This creates a de facto synthetic dollar position in which the BCB pays the onshore dollar rate (Cupom Cumbial) and the exchange rate variation at maturity, and receives the daily compounded SELIC rate. The BCB is effectively short dollars, with a reverse swap indicating that the central bank is long. The FX swaps are effectively sterilised such that the money supply and foreign currency reserves are unhindered. The transactions are also more flexible than trading spot since the intervention is temporary – the swaps can either be rolled-over or left to expire. Although this form of intervention limits pressure on foreign reserves, investors still look to the central bank’s stockpile of hard currency to collateralise the swap since settlement in BRL ensures a degree of convertibility risk.

Fig 7. BCB Monthly FX Interventions, USDbn

Source: MNI, Bloomberg, BCB

|

![]()